The Greece-China Connection

Apollo of Piraeus

|

||

|

Apollo of Piraeus: The most ancient life-sized bronze statue. Originally it must have shone like gold. |

||

|

b. Small fragment of a rein, preserved by happy coincidence in the right hand of Apollo, constitutes the statue’s identity card: Charioteer. In its left hand, the fragment of a whip. |

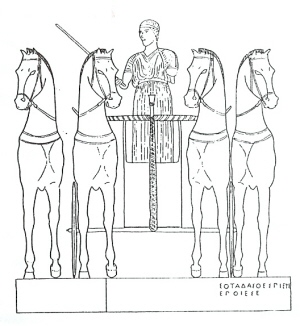

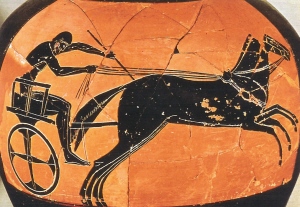

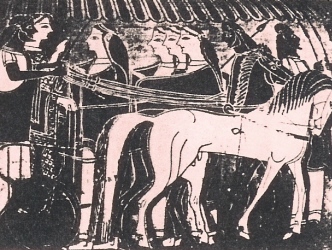

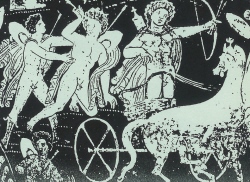

Drawings depicting Apollo as Charioteer. To its left there was possibly another figure, perhaps Nike. (Drawings by painter Lilly Kristensen) |

|

|

The Charioteer of Delphi: Naked and Robed Charioteers

The Delphi Charioteer with two reins in his hand (the third was removed for restoration). Photo, 1987 The Delphi Charioteer was found in 1896 in three sections: the head and torso to the waist, the rest of the body, and the right arm with three reins held in the hand (from the article written by Francois Chamoux, Professor at Nancy, 1955). Chamoux considers it possible that there was another figure standing next to the charioteer. |

Reconstruction of the Delphi Charioteer’s chariot, by Roland Hampe (Munich, 1941). However he was probably standing more to the right, and on his left there was another figure, probably Nike. Most likely he was also holding a whip in his left hand, together with the rudder of the chariot. According to myth, Kekrops had introduced the four-horse chariot, and “his image was set among the stars as the constellation Auriga.” |

|

|

The hand of the Delphi Charioteer, half-open to release the reins.

The sole of the foot of Apollo of Piraeus. The bosses have broken off. |

||

|

The soles of the feet of the

Delphi Charioteer with bosses to be fixed |

||

|

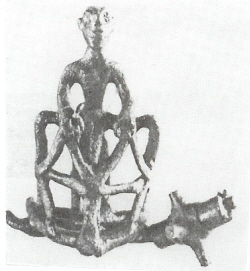

Bronze naked charioteer from Olympia. His chariot is made out of tree branches. 8th c B.C., Olympia Museum. The belief is well-established that after the geometric period (later than 800 B.C.) there were no more naked charioteers. But no one seems to have stated that god and hero charioteers (with a few exceptions) continued to appear naked throughout the archaic and classical periods, with only a short cloak around their shoulders or waist. Only professional charioteers wore a long (usually) chiton – in most cases white – with long or short sleeves. |

The horseman Rampin (his head is part of the Rampin collection in the Louvre) 81 cm, Marble, 550 B.C.The earliest marble statue known of such a large horseman. Acropolis Museum. He is naked, as an archaic kouros and as a geometric charioteer. Gods and heroes continue to be naked as charioteers after the geometric period (800 B.C.) |

|

|

The “jockey boy” of Artemision, 2nd c. B.C. He is wearing a short chiton with no sleeves. In his left hand, the fragment of a rein; in his right, the fragment of a whip. Athens Archaeological Museum. |

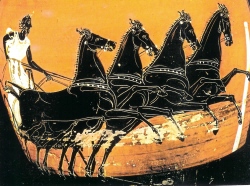

Black-figured vase in the British Museum with charioteer wearing the professional sleeveless uniform. |

|

|

|

(left) One of the 7,000 clay figures of the Army of Qin-Shi-Huang-Ti found in his grave (foot-soldiers, archers, etc.). Museum of Xian. The posture and expression of certain charioteers made me think of the statue of Apollo, and that it was very likely not an archer, but a charioteer. I began to look for evidence, and the first thing that drew my attention was a small, flat and narrow bronze piece attached to the statue’s palm, that could be the fragment of a whip. |

|

|

Charioteers holding the whip in the left hand

Country chariot driven by two mules. Black-figured vase, London British Museum. The driver has all four reins in his right hand, and holds the whip in his left. |

||

|

Wedding procession on a Corinthian krater (about 600 B.C.) Rome Vatican Museum. The whip is held in the left hand.

|

The wedding of Cadmos. Black-figured vase (about 500 B.C.) in the Louvre. Cadmos is holding the whip in his left hand. |

|

The Champion’s Band |

||

|

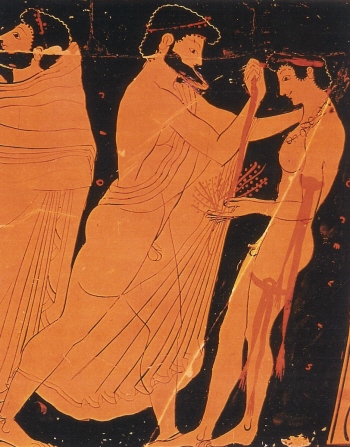

The umpire puts a band around the head of a champion, who is wearing similar bands around the arm and thigh. Red-figured vase, Munich Antikensammlungen. At the Siao Lin Tower, even today, wrestlers receive similar bands for the forehead. |

The Charioteer of Delphi. He is wearing the champion’s band. |

|

|

“Macao returns to China in the year 2000.” During the celebrations, the Dragon Dance dancer / heroes wore red ribbons, not only around their forehead, but also around the arm, like the Olympia champions. Millions of people (Chinese, American, European; University professors, scholars) saw this picture, but it seems only Theresa Mitsopoulou has connected it to the lone Greek vase in Munich. |

Apollo of Piraeus. A band around his head, and little holes to affix a wreath. |

|

|

The red Chinese and Greek band on the forehead could be explained as a coincidence but the ribbon around the arm has certainly been copied from an original pattern. Original man used to decorate his head, neck, face, cheeks, breast, arms, waist, thight and ankles with real snakes. He was given the snake as a price and guardian because snakes at the rats that caused the plague. A big snake used to reside inside the acropolis and the priests used to feed it. In India the Hindus feed the naga and in certain parts of Greece a snake in the house is reguarded as a protector and will not be killed. In a unique stone relief in an Indian temple, a king is crowned by Siva with a snake and a statue of Aphrodite with a snake around her thigh. |

||

|

Relief from Gangaikondakolapuram, India. Temple Brihandiswara. 11th c. King Kola is crowned by Siva |

The statue of the Goddess Athena inside the Parthenon. On her Aefia are vipers and the head of Medusa. On her left is a big viper. Her bracelet is an imitation of a snake. Most jewelry and belts of today have snake symbolism. Her belt is made of snakes and there are snakes wrapped around her upper arm. |

|

|

Terracotta statue of Aphrodite with a snake around her left arm and a snake on her left thigh from the 2nd century BC. Turkey Canakkule Museum.

|

The stripes on the upper sleeves of modern jackets and sweaters are the memory of the snake symbolism. Everything has an explanation and we copy the same symbols of the past without realizing their meanings anymore.

Modern jackets, sweaters and t-shirts with the fabric finish of the neck and the stripes on the upper sleeve, like those on the arms of the Goddess Athena, symbolize the snake and is a protection against evil.

|

|

Apollo and other gods and heroes as naked charioteers |

||

|

Apollo as naked charioteer. His chariot is driven by snakes. Red-figured vase in Munich. Gods and heroes depicted as charioteers did not wear the professional “xystis,” but instead were almost naked with a short cloak on their back. |

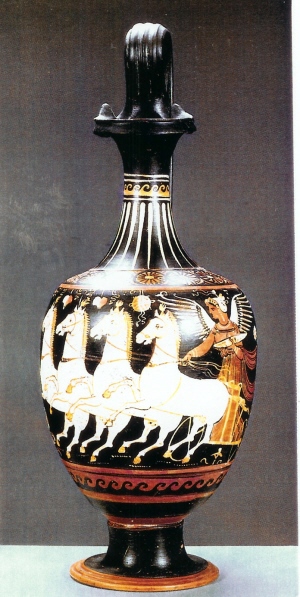

Apollo as naked charioteer. His chariot is driven by swans. |

|

|

Apollo – charioteer, naked with only a chlamys around his shoulders. Apulian krater (350 B.C.), Baltimore. Apollo was often depicted as an Archer holding a bow, and usually had a phial (a shallow vessel for libations) in his right hand. |

Apollo as naked charioteer. His chariot is driven by ducks. Etruscan ring seal (3rd c. B.C.), Berlin. |

|

|

Zeus as naked charioteer. Gigantomachia. Apulian krater (350 B.C.), Petrograd Hermitage Museum. |

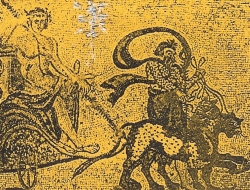

Dionysus as naked charioteer. His chariot is driven by panthers. Mosaic (3rd c. B.C.) Cyprus. |

|

|

Pluto abducts Persephone. Apulian krater (350 B.C.), London British Museum. |

||

|

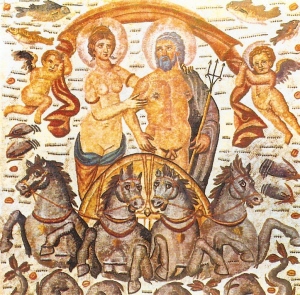

Poseidon and Amphitrite, detail, Roman mosaic, Louvre Museum, Paris. |

Poseidon as naked charioteer. His chariot is driven by seahorses. His chlamys is in the air above him. Mosaic (around 300 A.D.) found in a house in Tunisia. |

|

|

Laius abducting Chrysippus. Red-figured vase in Berlin. |

The figure beside the charioteer was a warrior or athlete, or simply a passenger. Base found in the Themistokleian wall of the Acropolis, Athens Archaeological Museum. A winged Nike waited for the winner of the race, holding a wreath…. |

|

|

The victorious moment (all four reins in one hand). Huge gold earring, probably from a statue from Euboea, 4th c. B.C., Boston Museum of Fine Arts |

A coin from Syracuse, British Museum |

|

|

Gold coin of Phillip II of Macedonia, Athens Nomismatic Museum. The charioteer holds all the reins in one hand before victoriously finishing the race. |

Apollo / Helios, from a Roman floor mosaic. All four reins in one hand (the left). |

|

|

Red-figured oinochoe from Apulia, 46 cm, around 315 B.C., Mannheim Reiss Museum. The Nike has all four reins in her right hand. |

||

|

Questions? E-mail Matt |

|

|

Help Support Matt's Greece Travel Guides |

|

A small fragment attached to the right hand

of Apollo of Piraeus poses the question…

A small fragment attached to the right hand

of Apollo of Piraeus poses the question…