Troy

Battle of Hercules and the Giants. Antonio del Pollaiuolo. 15th cen. Metropolitan Museum

Herakles now began the last phase of his career, a period comprised for the most part of attempts to gain revenge from all those who had cheated him, abused him, or in any way become his enemy.

He first sailed to Troy, taking with him an army of volunteers in eighteen (or six) fifty-oared ships; his motive was to punish Laomedon, king of Troy, for refusing to hand over the promised mares when Herakles slew the sea-monster and rescued the princess Hesione during his ninth labor. When they landed at Troy, Herakles left Oikles, the grandson of Melampous and father of Amphiaraos, to guard the ships while he laid siege to the city. Laomedon and his army made a sudden attack on the ships and Oikles was killed, but Herakles drove them back inside Troy and eventually broke through the walls. Telamon, Herakles’ favorite companion, ran through the breach into the city, but Herakles, enraged that anyone would enter before him, drew his sword and rushed to kill him. Telamon, as quick at thinking as at running, realized that he had stolen Herakles’ glory and quickly began to gather stones. When Herakles asked what he was doing, he replied that he was building an altar for Herakles Kallinikos (“Herakles the Glorious Victor”). Herakles not only forgot his anger but also, when the war was won and Laomedon and all but one of his sons had been killed, gave the princess Hesione to Telamon as his prize. The sole surviving son was Podarkes, who was sold into slavery, but Herakles allowed Hesione to ransom him with whatever she chose. She took the veil from her head and used it to buy her brother, whose name from then on was Priamos (from the Greek word priamai, “buy”).

We would expect Herakles to claim Hesione as his own prize after killing her father; perhaps this is why Pindar has Telamon, not Herakles, kill Laomedon. But Herakles had earlier asked Laomedon for horses, not his daughter, and his current action accords with his tendency to abandon or give away the women he wins.

Herakles’ jealous rage at Telamon’s heroism is reminiscent of Achilleus’ prayer that the Trojan War would end with only Patroklos and himself alive, so that they would not have to share the glory of victory with the other Greeks. These actions of the two great heroes are typical of the combination of narcissism, jealousy, and competitiveness which is such a marked characteristic of Greek myth and culture; honor and glory, the highest goals of mythic hero or Greek citizen, seem to be limited and fixed quantities that cannot be shared and that one wins only if another loses.

While Herakles was sailing back from Troy, Hera sent the god Hypnos (Sleep) to make Zeus fall asleep while she attempted to destroy Herakles with great storms. When Zeus awoke, he rescued Herakles and hung Hera from Olympos with anvils attached to her ankles. Herakles sailed to the island Kos, but the natives thought he was a pirate and fought against him.

In another version of these events, Herakles lost five of his six ships in the storm; finally driven to Kos, he met a shepherd, the king’s son Antagoras, and asked him for a ram. Antagoras proposed that they wrestle for the ram, but the match soon grew into a great battle between Greeks and Meropes (an early name for the people of Kos). When he could fight no longer Herakles fled to the house of a Thracian woman and put on her clothes to hide from his enemies. Later he defeated the Meropes and married Chalkiope; since he wore a dress decorated with flowers at the wedding, Koan bridegrooms from then on wore women’s clothing.

At this time, according to Apollodoros, Herakles came to Phlegrai and fought on the side of the gods in their great war against the Giants. An oracle had informed the gods that the Giants could only be killed by a mortal who was an ally of the gods, and Zeus chose Herakles.

Apollodoros alone explains this as due to the duplicity of the Molionids, who

attacked the army while Herakles was sick.

Elis

The next target for Herakles’ vengeance was Augeias of Elis, who had

refused to pay Herakles for cleaning his stables in the fifth labor. When

Augeias learned that Herakles was coming with another volunteer army, this time

from Arcadia, he appointed his nephews (or sons, or Poseidon’s sons) Eurytos and

Kteatos to lead the Elean army. These two, who were called the Molionids for

their mother Molione, were said to have been born from a single silver egg;

either their two bodies were somehow joined together, or they had two heads,

four hands, four feet, and one body apiece. Since the Molionids were the

strongest men of the time, Herakles’ army was regularly defeated. When a truce

was called for the celebration of the third Isthmian games, Herakles ambushed

the Molionids on their way to the festival and killed Eurytos or both.

Returning to Elis he captured the city and killed Augeias and all his sons

except Phyleus. Since Phyleus had earlier supported Herakles in his claim

against Augeias and had been thrown out of the country along with him, Herakles

now brought him back and made him king of Elis.

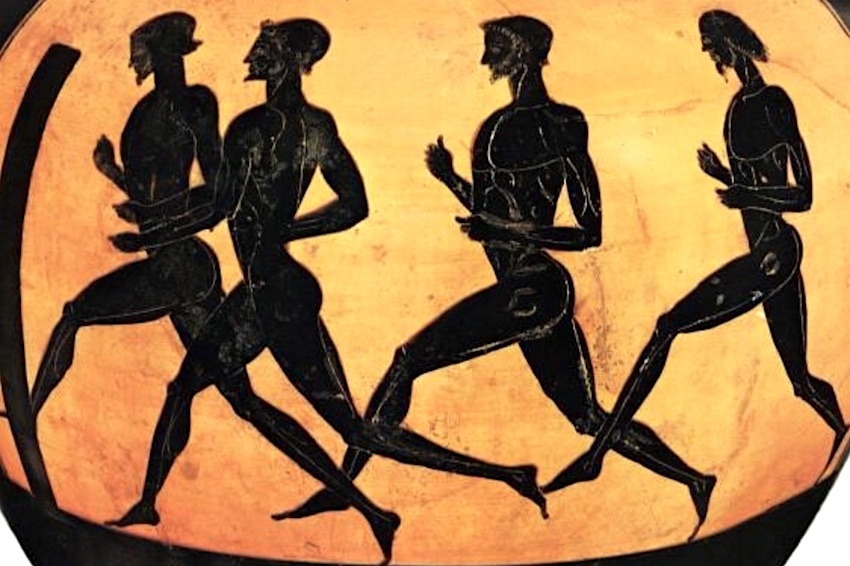

Most sources say that Herakles used the spoils of his victory over Augeias to institute the Olympic games at Elis. Near the tomb of Pelops (his great-grandfather) he built six altars for the twelve Olympian gods (the usual list of the twelve gods includes Zeus, Poseidon, Hera, Demeter, Hestia, Apollo, Hermes, Hephaistos, Ares, Artemis, Aphrodite, and Athena; Zeus tried to enroll Herakles after his death as one of the twelve but Herakles refused, since his acceptance would require the expulsion of one of the previous twelve). Diodoros (who has Herakles invent the games after his seventh labor) says that Herakles was the only contestant in each event, and Tzetzes says that when no one dared to wrestle with Herakles, Zeus himself assumed the appearance of a mortal, wrestled Herakles to a draw, and then revealed himself to his son. Both Pindar and Pausanias, however, give lists of the various victors in the Olympic games held by Herakles.

A different tradition, which Pausanias learned in Elis itself, held that the Herakles who founded the Olympic games was not the son of Zeus and Almena, but an earlier figure named Herakles the Daktyl. In these first games Zeus defeated Kronos in wrestling, and Apollo beat Hermes in a race and Ares in boxing. Fifty years after Deukalion’s flood a descendant of Herakles the Daktyl named Klymenos came to Greece from Crete and first held the games at Olympia in Elis. The nest to hold the games was Endymion, and other notable Olympic games were held by Pelops, Amythaon, Pelias and Neleus, Augeias, and finally Zeus’ son Herakles, who also won the wrestling event.

The Daktyls were archaic demons, magician-gods similar to the Korybantes, Kouretes, and Kabeiroi and associated with both Phrygia and Crete. Both Strabo and Diodoros say that the Cretan Kouretes were descendants of the Daktyls, and Pausanias equates the Daktyls with the Kouretes who guarded the infant Zeus in a Cretan cave. Diodoros says there were ten (or a hundred) Daktyls; born in Phrygia (home of the Korybantes), they went to Samothrace (home of the Kabeiroi), where they taught mysteries and initiation rites to Orpheus, then went to Crete (home of the Kouretes), where they discovered fire and invented metallurgy. Pausanias says that the Daktyls came originally from Mount Ida in Crete (rather than Mount Ida in Asia Minor), and that there were five of them: Paionaios, Epimedes, Iasios, Idas, and Herakles, the eldest. This Herakles arranged for his brothers to run a race, and crowned the victor with an olive branch.