The Final Labors of Herakles

The last four labors are quite different from the first four. They take

Herakles to imaginary lands and peoples beyond the known world and (partly

because of the great distances he must go) involve him in a large number of

secondary adventures during his travels.

The Belt of Hippolyte

Nicolaes Knüpfer - Hercules Obtaining the Girdle of Hyppolita. 17th cen

The ninth labor was to bring back the belt of Hippolyta, queen of the Amazons, a warlike race of women who lived on the shores of the Black Sea. Herakles enlisted a volunteer crew and sailed to the far east coast of the Black Sea where the Amazons were camped. Hippolyte met him on the shore and agreed to give him her belt. But once again Hera intervened; disguised as an Amazon, she came to the other Amazons who were watching the scene below on horseback from a hill above the shore. Hera told them that the stranger was about to carry off their queen, and the Amazons raced down the hill and began a battle with Herakles and his crew. Many Amazons died in the confliuct, including sometimes the queen Hippolyte herself, and Herakles sailed off with the belt.

As he sailed through the Dardanelles to the Aegean sea, Herakles stopped at Troy and learned that king Laomedon had offended the gods Apollo and Poseidon by not paying them for fortifying the citadel of Troy. The two gods sent a plague and a sea-monster, and oracles told Laomedon that he would be released from punishment only if he sacrificed his daughter Hesione to the sea-monster. Herakles now saw Hesione in chains on the coastal rocks, about to be killed by the monster (just as his ancestor Perseus had seen Andromeda in Ethiopia), and he offered to save the princess. However, unlike Perseus, who had asked for the hand of Andromeda in return for saving her, Herakles promised to save Hesione if Laomedon would give him the prized mares which he had received from Zeus as compensation for Zeus' abduction of Ganymede, Laomedon's beautiful son. Laomedon agreed to this and Herakles saved Hesione, but Laomedon refused to give up the horses and Herakles was forced to leave.

How is this labor an impossible task? A woman’s belt (or, as it is often translated, “girdle”) commonly had a sexual significance in Greek and Roman myth and poetry; “to loosen a woman’s belt” meant to take her virginity. Thus Herakles’ ninth labor is essentially a representation of a sexual test. He must acquire the token which proves that he has won in a sexual encounter with the queen of the Amazons, presumably of all women the one most resistant to male overtures, the one most difficult to conquer sexually.

Herakles wins Hippolyte, and then kills her, just as he won the Trojan princess Hesione but asked for a pair of horses instead, and as he killed his wife Megara (or gave her to his lover Iolaos), and as he will give Hesione to Telamon and, especially, his concubine Iole to his son Hyllos.

Herakles’ fondness for women of the Amazon type (his next wife will be

Deianeira, a famous warrior and huntress) would seem to be an extreme example of

his general preference for non-maternal women, no surprise for the hero most

subject to recurrent persecution by a maternal figure (Hera). On a cultural

level the same sort of anxiety about maternal or sexually mature women (an

anxiety embodied in the head of Medousa) may help to explain not only why Greek

males were led to invent the myth of the Amazons (or Medousa) but also related

cultural phenomena (e.g., the cultural restrictions imposed on women, the

significance of homosexuality, etc.). Because of this anxiety Herakles cannot

have a lasting relationship with any woman; the woman who loses her virginity

must inevitably become maternal, and the Amazon must become Hera.Thus the

many women in Herakles’ life, like the labors themselves, are trials, occasions

for him to prove his strength, courage, and virility; that he kills them, leaves

them, or gives them away as soon as the test has been passed demonstrates not

only his inability to deal with mature female sexuality (the desirable virgin

becomes the feared woman) but also the insatiablity of Hera’s demands and the

futility of Herakles’ repeated attempts to appease her.

In Greek myth (or mythical history) there were three divisions of Amazons:

Skythian, Libyan, and those living by the Thermodon River at the east end of the

Black Sea. They were generally regarded as the daughters of Ares and the Naiad

nymph Harmonia or of an incestuous union between Ares and his Amazon daughters.

Since the Amazons were frequently said to remove their right breast by

amputation or burning, to facilitate archery and javelin-throwing, their name

was popularly derived from a-mazos (“without breast”).

Nevertheless the

Amazons appear in art with both breasts intact, often with one exposed (the

battle between the Amazons and the Athenians was one of the most popular

subjects sculpted on the friezes and pediments of Greek temples). The name

probably refers to symbolic rather than actual loss; Amazons were women who

renounced a woman’s role and maternal functions (like the goddesses Athena and

Artemis) and chose to conduct themselves like men. As Strabo says, belief in

the Amazon myths “is the same as as saying that the men of old were women and

the women were men.”

The Amazons appear most frequently in Greek myth and

art as fighting the Greeks; in addition to their war against Herakles, the

Amazons fought against Bellerophon, at some very early time against Dionysos,

and against the Athenians. Pausanias also says that the Amazons stopped at

Ephesos (on the Aegean coast of Turkey) to offer sacrifice to Artemis on three

occasions, when fleeing from Herakles and Dionysos and while on their way to

attack Theseus in Athens.

The Cattle of Geryon

Hercules and the Cattle of Geryones By Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder - Unknown author, Public Domain

Herakles’ tenth labor was to bring back the cattle of Geryon, a triple-bodied warrior who lived on Erytheia, an island in the Atlantic ocean off the coast of Spain. The cattle were guarded by the giant herdsman Eurytion and by Orthos, a two-headed dog whose parents were Echidna and Typhon and whose children, by his mother Echidna, were the Nemean lion and the Theban Sphinx.

During this labor Herakles made a circuit of the Mediterranean, going first to Crete, where he killed all the wild animals, then crossing to north Africa, across the Strait of Gibraltar to Spain, and returning through Europe. While in the African desert he became irritated at Helios (the sun) for making him hot and shot arrows at the god; impressed by this bravado, Helios gave Herakles a golden cup with which to cross the ocean (presumably the same cup Helios used to sail back each night from his landing place in the west to his starting point in the east). At the western end of the Mediterranean Herakles erected the Pillars of Herakles, and sailed across to the home of Geryon. After killing Orthos, Eurytion, and Geryon, he sailed back with the cattle to Tartessos on the Spanish mainland, returned the cup to Helios, and set off through Europe.

In Liguria (southeast France/northwest Italy) he killed two of Poseidon’s sons, who tried to steal his cattle; during the battle with the Ligurians, Herakles ran out of arrows, but Zeus rained down a shower of stones which Herakles used to defeat his enemies. When one of the bulls escaped and swam to Sicily, where Poseidon’s son Eryx put it in his herd, Herakles followed and killed Eryx in a wrestling match.

When he came to the Ionian sea, Hera sent a stinging fly (the Oistros) to bother the cattle; they ran away, with Herakles in pursuit, to the part of Skythia north of the Black Sea. Here, according to Herodotos, Herakles awoke one morning to find that his chariot-horses had disappeared; he came to the cave of a viper-maiden (a woman from the buttocks up and a serpent below), who told him that she had the horses but would not give them back unless he spent the night with her. Herakles stayed long enough to have three sons by the viper-maiden, who finally returned his horses and asked him what she should do with their children. Herakles gave her a bow (he always carried two) and a belt with a small gold cup attached, and showed her how he strung the bow and put on the belt; he then told her to send away any of the boys who could not duplicate what he had done. When the children grew up she named the eldest Agathyrsos, the next Gelonos, and the youngest Skythes, and tested them as Herakles had instructed. The first two failed the tasks, but Skythes succeeded and became the eponymous ancestor of the Skythians, who ever afterwards wore belts with little cups attached, in honor of their ancestor Herakles.

Diodoros gives two variant explanations of the Pillars of Herakles: either the entrance into the Atlantic was once very wide and Herakles narrowed it by extending the two continents, so as to keep sea monsters out; or the continents were previously joined and Herakles cut a channel, connecting the Mediterranean with the ocean.

Diodoros also says that Herakles, after passing through Liguria and Tyrrhenia (Etruria, home of the Etruscans), camped at the future site of Rome on the river Tiber, then fought a war with men called Giants at the Phlegraian plain near Mount Vesuvius. In Roman myth it was at this time that Herakles killed the monster Cacus, who stole some of Herakles’s cattle and dragged them backwards by their tails to his cave, so that Herakles could not follow their tracks. Diodoros continues that Herakles swam from Italy to Sicily while holding onto a bull’s horn; he then walked around the entire island (apparently not realizing that he had made a wrong turn in his journey from Spain to Greece) while nymphs created warm baths for him; Eryx challenged him to wrestle, demanding the cattle if Herakles lost; when Herakles demanded that Eryx wager his land, Eryx protested that the land and cattle were not of equal value, but Herakles replied that the cattle were invaluable since without them he would have to forfeit his claim to immortality; after defeating Eryx Herakles gave the land to the natives to hold in trust for one of his descendants (this is the city Herakleia, founded by the Spartan Dorieus and eventually razed by Carthage); he conquered the Sikanoi in the interior of Sicily, dedicated shrines to both his late opponent Geryon and his nephew Iolaos (who was with him), and at Agyrion first accepted honors and sacrifices as if he were a god (he began to be convinced of his future immortality when he noticed that both he and the cattle left footprints in the hard rock); he then went back to Italy and around the Adriatic coast to Greece.

When Herakles finally arrived in Greece with the cattle, one last

obstacle awaited him; a giant herdsman named Alkyoneus attacked him, either at

the Isthmus of Corinth or in Thracian Phlegrai. Herakles is sometimes regarded

as accompanied by an army at this time; after Alkyoneus crushed twelve chariots

and twenty-four warriors with a stone, he was killed by Herakles and Telamon.

According to Diodoros Herakles civilized the peoples of western Europe as he

passed from Spain to Italy; he founded the city of Alesia in honor of his

wanderings and built a highway through the Alps in order to enter Liguria. In

Aeschylus’ lost Prometheus Unbound Prometheus, while giving Herakles

directions on how to get from the Caucasus to the Hesperides, also predicts what

will happen to Herakles in Liguria: he will be attacked by natives trying to

steal his cattle and will run out of arrows; he will try to find stones to throw

but will fail, since the ground of Liguria is soft mud; Zeus will pity him and

send down a hail of round stones which Herakles will use to defeat the

Ligurians.

In response to Posidonios’ objection that it would have been

better for Zeus to rain down the stones on top of the Ligurians rather than

require Herakles to throw them, Strabo says with equally acute logic that it

would also have been better for Paris, the seducer of Helena, to have been

punished on his way from Troy to Sparta instead of afterwards.

Herakles’ encounter with the viper-maiden reflects and clarifies previous

symbolic elements in the myth. Although Herakles’ labors have multiple

determinants and levels of meaning, a recurrent theme is his attempt to

demonstrate masculinity and potency, to meet and overcome sexual challenges

(e.g., the daughters of Thespios, the Amazon queen).

There are furthermore

several indications that Herakles’ affair with the viper-maiden is really an

attempt on his part to prove himself equal to his father Zeus (and especially to

Zeus’ performance on the night he spent siring Herakles): (1) in one version

Skythes is the son of the viper-maiden and Zeus, not Herakles; (2) Zeus’

threefold extension of the night he spent with Alkmena, a metaphor for his

prodigious sexual ability, is recalled (and enlarged upon) by Herakles staying

with the viper-maiden long enough to father three children; (3) having

accomplished his task, Herakles leaves with the viper-maiden the weapon with

which he kills his enemies and a belt with a cup attached; when Zeus came to

Alkmena, he did two things before having sex with her: he told her of the

enemies he had (supposedly) killed and he gave her a cup.

The Golden Apples of the Hesperides

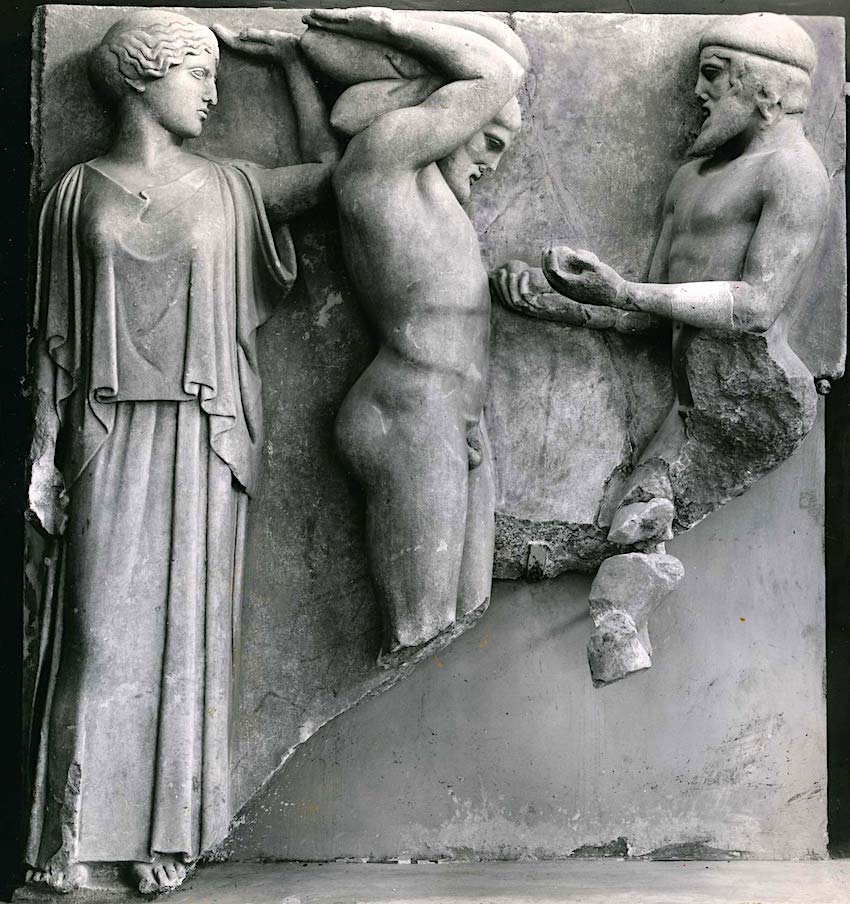

Marble metope from the east end of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, c. 460 BCE; in the Archaeological Museum, Olympia, Greece.

Herakles’ eleventh labor was to bring the golden apples from the garden of the Hesperides. The Hesperides were three (or four) beautiful nymphs, daughters of Nyx (Night); the literal meaning of their name is “daughters of evening (hesperos).” Their garden is one of the several paradises in Greek myth, and is located by Hesiod somewhere beyond the Ocean, by Euripides in the far west, by Hyginus in northwest Africa, somewhere beyond Mount Atlas in Morocco, and by Apollodoros in the far north among the Hyperboreans. The golden apple tree had been a wedding gift from Gaia to Zeus and Hera, and Hera had placed it in the garden, where it was guarded by a hundred-headed serpent named Ladon (each of whose heads spoke a different language). At the entrance to the garden stood the giant Atlas, who supported the sky on his head and shoulders. In Ovid’s version, the golden apple tree belonged to Atlas, who had received an oracle from Themis warning him that Zeus’ son would steal the apples and so put the serpent on guard. When Perseus arrived at Atlas’ home after killing Medousa, Atlas thought the oracle was being fulfilled and tried to force Perseus away; Perseus therefore used Medousa’s head to change Atlas into a mountain so huge that the heaven rested upon its summit.

In Macedonia, by the river Echedoros, Ares’ son Kyknos challenged Herakles to fight but a thunderbolt fell between the combatants and ended the contest. Like Perseus, who needed the help of three nymphs to discover where the Gorgons lived, Herakles now met certain nymphs, daughters of Zeus and Themis, who told him where to find Nereus, an old sea god who knew the location of the Hesperides. Herakles seized Nereus and held him tightly, although he changed into many shapes, until he told him where the Hesperides lived.

Herakles now came to Libya and was challenged to a wrestling match by Antaios, a son of Poseidon and Gaia who used the skulls of strangers he killed to make a roof for the temple of his father Poseidon. Every time Herakles threw Antaios to the earth, he arose stronger than ever (from contact with his mother Earth); finally Herakles held him up in the air and killed him by breaking his back.

In Egypt Herakles was captured by the king Bousiris, son of Poseidon and grandson of Epaphos; some time earlier, during a plague in Egypt, the Greek prophet Phrasios had advised Bousiris to sacrifice strangers and the success of this strategy had persuaded Bousiris to sacrifice all strangers who came to his country (including Phrasios). However Herakles, like Samson among the Philistines, broke his chains at the altar and killed both Bousiris and his son.

After leaving Egypt Herakles came to Rhodes, where he stole an ox from a cattle-driver’s wagon, sacrificed it, and ate it, while the unfortunate driver stood on a hill nearby and cursed. For this reason, says Apollodoros, sacrifices to Herakles are accompanied by ritual curses. He also went to Arabia (or Ethiopia) where he killed the king, Tithonos’ son Emathion.

At some time during his travels Herakles came to the Caucasus and freed Prometheus from his punishment by shooting the eagle which was eating the Titan’s liver. To commemorate the bonds of Prometheus, Herakles put on a wreath of olive. This wreath, which Herakles made the prize of the Olympic Games, is evidently a symbolic replacement for the chains which had bound Prometheus; since Zeus’ decision to punish Prometheus eternally could not be rescinded, some symbolic continuation of it had to be devised. Hyginus has a similar explanation for the custom of wearing rings made of stone and iron. The usual reason given for Zeus’ willingness to allow the release of Prometheus is his need to know the name of the woman whose son could overthrow him, a secret known only to Prometheus (the woman, as Prometheus will tell Zeus after he is freed, is Thetis).

When he finally arrived at the garden of the Hesperides, Atlas told him that only he was allowed to touch the apples and that Herakles would have to hold up the sky while Atlas picked the apples. Herakles agreed and Atlas went for the apples; when he returned, not wishing to take back the sky, he said he would take the apples to Eurystheus. Herakles, who had been forewarned by Prometheus, pretended to agree but asked Atlas to hold the sky for a moment while he put a cushion on his head; when Atlas took the sky, Herakles picked up the apples and left. After Eurystheus received the apples, he gave them back again to Herakles, who gave them to Athena; the goddess returned them to the Hesperides, since only they were allowed to possess them.

Two of Herakles’ primary motives, the attainment of immortality and the

search for maternal nurturance, are embodied in the eleventh labor. On one hand

the magic fruit in the paradise garden, like the golden apples of north European

myth or the fruit of the Tree of Life in Genesis 2, are a means to immortality;

for the same reason the streams of the garden of the Hesperides flow with

ambrosia, the food of the gods and the source of their immortality. On the

other hand both the apples and their location represent the idyllic existence of

the infant at its mother’s breast; the garden of the Hesperides, like the garden

of Eden and other paradise gardens, is a symbolic state of abundant maternal

nurturance. Herakles’ winning of the apples is one of several attempts he makes

to obtain this nurturance, the denial of which was graphically portrayed in the

episode of Hera rejecting him from her breast.

The earliest full account of this labor is a fragment of Pherekydes: Gaia gave

a golden apple tree to Zeus when he married Hera, and Hera asked that it be

planted in the garden near Mount Atlas; when Atlas’ daughters kept stealing the

apples, Hera set the serpent to guard them; Pherekydes then tells of the nymphs

and of Herakles’ struggle with Nereus, who changed into water and fire before

resuming his true appearance and disclosing to Herakles the location of the

apples; Herakles went to Libya and killed Antaios, then to Egypt, where he

killed Bousiris and his son, herald, and servants at Memphis; from Egyptian

Thebes Herakles went back through Libya, sailed through the ocean to Prometheus,

for whom he killed the eagle as it flew overhead, then came to Atlas and

followed Prometheus’ instructions.

Apollonios has Herakles kill the

guardian serpent and take the apples himself; he then grew thirsty and kicked a

rock, from which a spring gushed. This story is told by the Hesperides to the

Argonauts and saves them from dying of thirst.

According to Herodotos Herakles went to the oracle of Ammon (the Egyptian Zeus), wishing to see his father. Not wanting to reveal himself, Zeus covered himself with a ram’s fleece and held the ram’s head in front of his face, and therefore the Egyptian Zeus is portrayed with a ram’s head. Herodotos, who believed that Herakles was originally an Egyptian god who had been taken over by the Greeks, also tells the story of Herakles and Bousiris but regards it as unbelievable.

The Greek word for apples (mela) is used metaphorically for “woman’s breast,” and the Greek word for brassiere is melouchos (“apple-holder”).. This is why golden apples are always associated in Greek myth with weddings (e.g., Zeus and Hera, Peleus and Thetis, Atalanta and Melanion), and why the earliest state of mythic humanity is so often a paradise of total bliss and contentment.

Kerberos

Heracles and Cereberus by Boris Vallejo

Herakles’ twelfth and final labor was to bring back Kerberos, the three-headed (or fifty-headed or hundred-headed) dog which stood before the house of Hades in the underworld and ate anyone he caught trying to escape. Herakles first went to Eleusis (30 miles west of Athens, the site of the Eleusinian mystery religion), where he was purified by Eumolpos, son of Poseidon and founder of the Eleusinian mysteries, for killing the centaurs during his second labor.

He then went to the entrance of the underworld at Tainaron, at the southern tip of the Peloponnese, or near Herakleia on the Black Sea, and entered Hades. All the souls of the dead fled in fear, except for Medousa and the hunter Meleager. Herakles tried to strike Medousa with his sword, but it was like stabbing air, since she was a phantom. He then fell in love with Meleager and started making advances to him. When Meleager told him, "Forget it, Herakles, I'm dead," Herakles asked Meleager if there was anyone like him in the world above, and Meleager told him about his sister Deianeira, a huntress whom Herakles will eventually marry.

While in Hades Herakles rescued Theseus, who with his friend Peirithoos had been imprisoned since they came seeking to win Persephone, but he was unable to release Peirithoos. He freed Askalaphos from the stone which Demeter had put on him because he informed on Persephone, but Demeter then turned Askalaphos into a horned owl. He killed one of Hades’ cattle so that the thirsty souls could have blood to drink and wrestled with Hades’ cowherd Menoites, breaking his ribs. Finally Hades told him he could have Kerberos if he defeated him without weapons; Herakles squeezed Kerberos around the head until the dog was exhausted. He exited from the underworld at Troizen, not far from Mycenae (or at Tainaron, Skythia, or Mount Laphystios near Koronea), showed Kerberos to Eurystheus and then took him back to Hades.

Herakles’ winning of immortality appears three times in this labor: successfully returning from Hades is itself a conquest of death, initiation into the Eleusinian mysteries promises a happy afterlife, and successful completion of the labors, as the Delphic oracle told Herakles, will make him immortal. The same motive (and reward) have already occurred in his drinking Hera’s milk, the hypothetical exchange with Cheiron, and his quest for the apples of the Hesperides).

Herakles was initiated into the Eleusinian mysteries by Mousaios, a legendary prophet and singer, and, since foreigners were prohibited from initiation into the Greater mysteries, the Eleusinians founded the Lesser mysteries specifically for Herakles, the benefactor of all mankind.