Oedipus

After Laios became king, he married Menoikeus' daughter, called Epikaste by Homer and Iokaste by later writers. Since an oracle had warned him not to have a son, he refused to have a sexual relationship with his wife. A version of the oracle appears in the ancient Hypothesis (Introduction) to Sophocles' play Oedipus Tyrannos: "Laios, son of Labdakos, you seek the gift of progeny: I will give you a son: but it is fated that you leave the sunlight by the hands of your son: for thus Zeus, son of Kronos, has decreed, moved by the hateful curse of Pelops, whose son you raped: all this he prayed for you."

The Finding of Oedipus by Johann Heinrich Keller (Swiss, 1692–1765)

For both Aeschylus and Euripides, the oracle is (as often) clearly conditional;if Laios should have a son, that son will kill him. In order to avoid this fate, Laios refrained from sex with Iokaste until, overcome by madness or drunkenness, he went to bed with her and fathered Oedipus. Laios then tried a second time to avert the curse of Pelops, by piercing his infant son's ankles with brooch-pins or ox-goads and giving him to a herdsman to expose in the mountains. But the herdsman to whom Iokaste gave the baby gave him in turn to a shepherd of king Polybos of Corinth, and the king and his wife Merope (or Periboia) raised the baby, named him Oedipus ("Swollen-Foot"), and pretended he was their own child.

In another version Oedipus was put into a chest and thrown into the sea; the chest washed ashore at Sikyon, where Polybos' wife Periboia, who was washing clothes on the shore, found Oedipus and raised him as her own.

When Oedipus was a young man, his friends resented his great strength, and told him he was not the son of Polybos. Or a drunk told him he was not Polybos' son, although Polybos denied this accusation. Or Oedipus guessed from the redness of his beard that he was someone else's son. In every case Oedipus left Corinth and set out for Delphi to ask the oracle about his parentage.

The Murder of Laius by Oedipus, by Joseph Blanc 1867, Paris, Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts

In one version Oedipus never made it to Delphi. While on the way he met Laios, who was also going to Delphi to find out if the child he had exposed was still alive, at the famous Triple Crossroad (where three roads led to Thebes, Corinth, and Delphi). Usually Oedipus goes to the oracle and learns, sometimes without asking, that he was fated to kill his father and marry his mother. Oedipus, still believing that the king and queen of Corinth were his parents, resolved never to return to them. When he came to the Triple Crossroad he was about to take the road east toward Thebes, instead of south to Corinth, when he met Laios.

Laios was accompanied by a charioteer and several attendants. When Laios or his charioteer ordered Oedipus to get out of the way, Oedipus refused. Laios then ordered his charioteer to strike Oedipus with his goad, or to drive the chariot wheels across Oedipus' feet (which were especially sensitive). In a rage, Oedipus pulled Laios from the chariot and killed him, as well as all but one of his companions. He then continued on to Thebes, leaving the bodies lie where they were.

Oedipus and the Sphinx, Françcois-Xavier Fabre. 1808, Dahesh Museum of Art

At Thebes Oedipus found the city in a state of crisis. A terrible female monster called the Sphinx (with the face of a woman, the body of a lion, and the wings and claws of a bird of prey) was sitting on nearby Mount Phikion, or on the walls of the citadel itself, and was asking any citizen who approached her this riddle: What is it that has one voice and goes on four legs in the morning, two at noonday, and three in the evening? The Thebans had learned from an oracle that they would be free of the Sphinx if someone could answer this question, but everyone who had tried so far had failed and had been eaten by the Sphinx.

The Thebans now learned from king Damasistratos of Plataia that he had found and buried the bodies of Laius and his companions. Kreon therefore offered both thekingship and the hand of the widow Iokaste to whoever could solve the riddle of the Sphinx. Oedipus volunteered, and told the Sphinx the answer was "Man, who crawls on all fours as an infant, walks on two legs as an adult, and uses a staff in old age." This answer was sufficient for the Sphinx, who jumped to her death from the citadel or from Mount Phikion (a strange means of suicide for a creature who could fly).

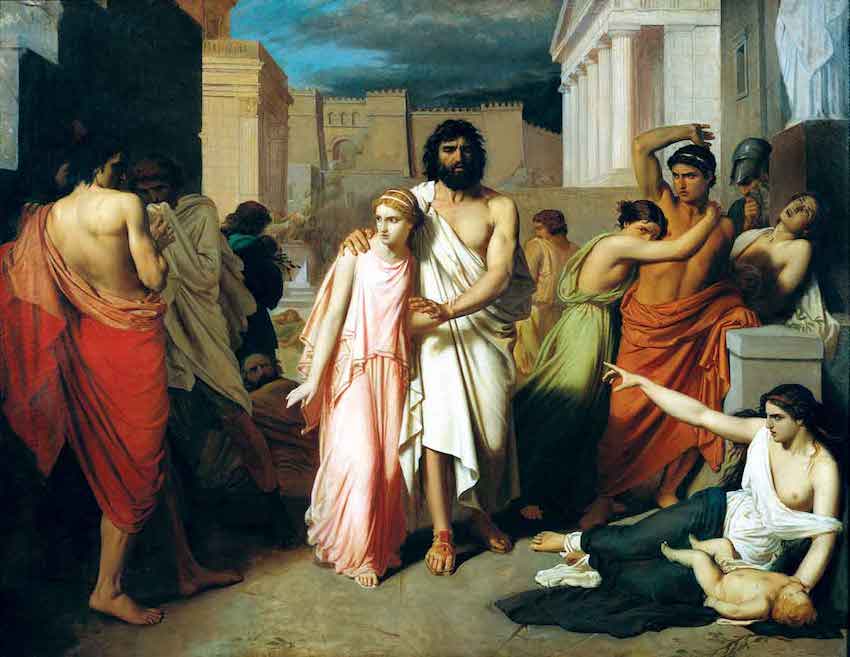

Oedipus and Antigone, or the Plague of Thebes, by Charles Jalabert, 1843, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Marseille © BridgemanImages

Oedipus now became king of Thebes and married his mother Iokaste; to the Thebans he was the smartest man in the world, since only he had known the answer to the riddle. Oedipus and Iokaste had four children, the daughters Antigone and Ismene and the sons Eteokles and Polyneikes.

The happy life of Oedipus and Iokaste was interrupted by a plague of barrenness which afflicted Thebes. Oedipus sent Kreon to Delphi to ask what they should do, and he came back with the answer that Thebes was being punished because they had not found and punished the murderer of the late king Laios.

What happened then is the subject of the world's first detective story, Sophocles' Oedipus Tyrannos. Although the prophet Teiresias urged Oedipus to drop the investigation, Oedipus finally discovered that it was he who had killed Laios and furthermore that Laios was his father and Iokaste was his mother. Oedipus drew his sword and rushed to Iokaste's chamber, but when he opened the door he found that she had hanged herself. He took the brooches from her robe and stabbed them into his eyes, blinding himself.

Jean-Antoine-Théodore Giroust - picture by alexmarie28, painting at the Dallas Museum of Art

Oedipus now went into exile, either self-imposed or ordered by Kreon in accordance with the punishment Oedipus himself had ordained for Laios' murderer. Before he left Thebes he cursed his sons for having said not a word against his banishment. He spent the rest of his life wandering through Greece as a blind beggar (since no city would allow him to stay), accompanied only by his faithful daughter Antigone. Finally he came to Kolonos (Sophocles' birthplace) in Athens, where an oracle had told Oedipus he would die and where king Theseus welcomed him and promised him refuge. Ismene came from Thebes and told Oedipus that Eteokles had driven out his brother Polyneikes, that war between the brothers was imminent, and that Kreon was coming to take Oedipus back to Thebes, since an oracle had declared that the land of Oedipus' death would be blessed by the gods. Kreon arrived and tried to kidnap Oedipus and his daughters, but was prevented by Theseus, who had made Oedipus a citizen of Athens. Polyneikes then came and asked for Oedipus' help, but Kreon protected Oedipus from his family, and again Oedipus cursed his sons, then walked (without his staff or the help of his daughter Antigone) into the sacred grove of Kolonos. Theseus heard the crash of thunder and a voice from the sky saying "Oedipus, why have you kept us waiting so long?", but when the Athenians searched they could find no trace of him.

This is what

happens to Oedipus in Sophocles'

Oedipus Tyrannos

and

Oedipus at

Kolonos. In

the very different version of Euripides'

Phoinissai

, Oedipus is not exiled but is kept as a blind

prisoner in the palace by his sons, whom he curses

for mistreating him. Iokaste does not commit

suicide until after the mutual fratricide of her

sons, when she stabs herself and falls on their

dead bodies; only then are Oedipus and Antigone

sent into exile. According to Homer,

Oedipus continued to rule in Thebes after the

death of his wife, although he was constantly

troubled by her Furies.