Xanthi

Photo By Georgios Tsichlis@shutterstock.com

|

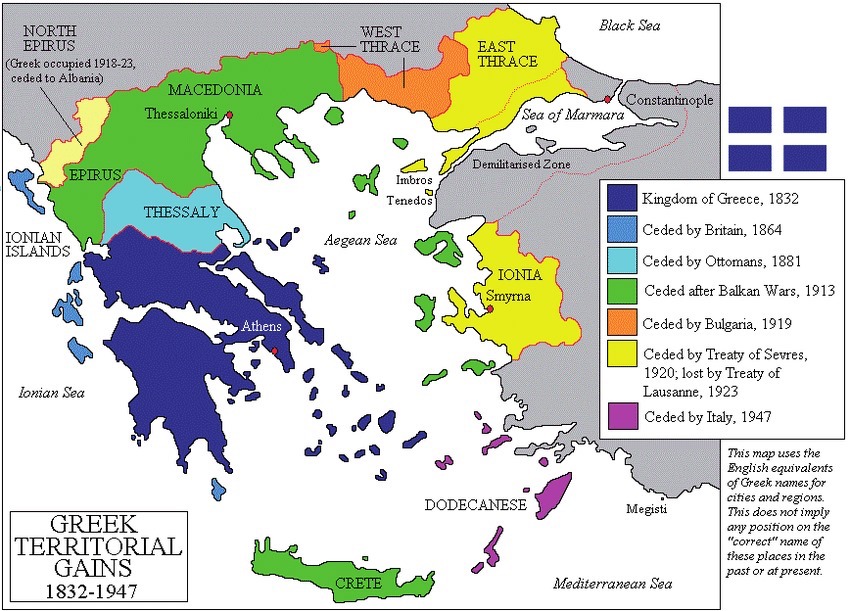

by Maria Verivaki After our adventure near Greece's tri-border (see Evros), we couldn't get enough of Thraki. We wanted to devour it. So we looked carefully at the map, trying to work out how we can get maximum value from our limited holiday time. Northwest of Thessaloniki, Greece feels like an island. Politically, in fact, it has always been treated as such: for nearly 40 years (1974-2012), there was a Ministry of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, and for the last ten years, it is a sub-ministry. EM+T is about twice the size of Crete, but it has about the same population as Crete, and it is also made up of sea and mountains, like Crete. We have never heard of a Ministry of Crete before, so why does EM+T get special treatment? If you think about how modern Greece developed, it all started with war. Without war, Greece would never have existed. Since the Greek people's fight for independence from the Ottomans in the 1820s, it took about a century of wars and concessions from other countries - with Greece suffering both gains and losses - for modern-day Greece to be formed. The EM+T region was 'Hellenistic' (culturally and linguistically Greek) since ancient times, but the region in general was also conquered and populated by other races and the main religion in the area before 1920 was Islam. When the Ottoman empire crumbled, EM+T were part of Bulgaria, which had access to the Mediterranean Sea in this way. In 1913, Greece won a large part of Macedonia according to the Treaty of London, and later in the same year, Eastern Macedonia, according to the Treaty of Bucharest, while in 1919, it also won Western Thrace according to the Treaty of Neuilly. We almost got Eastern Thrace too, but that eventually went to Turkey according to the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923. |

|

|

|

The Treaty of Lausanne had much wider consequences than just a land grab. It defined the Greek and Turkish borders, but it also entailed that Moslems were forced to leave Greece (~ 450,000 people), and Christians were forced to leave Turkey (~ 1,200,000), EXCEPT in two areas that were deemed 'special': Western Thrace which was now Greek and Moslems were allowed to stay, AND Constantinople/Istanbul which was Turkish and Christians were allowed to stay (they could choose which country they would eventually settle in). The population exchange was based on religious affiliation rather than national identity. Greeks weren't the only Christians in the region; there were also Armenians, for example. And Moslems weren't only the Turks; there were also the Pomaks, and some Roma (in Crete, the Roma are Christian). Bearing all this in mind, its now easy to understand why EM+T gets special treatment; historically, it has been the most "traded" part of the country, with the greatest mixture of cultures, given its land borders, ending up in Greek hands after a series of wars, occupations and governments which shaped the region. Moslems were the main religious group living in Thraki (as we call Western Thrace) before the Treaty of Lausanne; thus, the term 'Moslem minority' was born, and all Moslems were clumped into one group, regardless of their language and culture. Since the population exchange, Moslems now number 1 in 3 people in Thraki. It is the only part of the country where the imam's call to prayer is still heard to this day, school teachers and mufti often come from Turkey and Sharia law was in fact practiced for marriage and property rights (but not for criminal cases) among the Moslem minority, until the beginning of 2018 when it was outlawed under the SYRIZA government - up until then, strangely enough, Greece was the only European country where Sharia law was being practiced and very few Greeks would have even known this. |

|

|

|

A hundred years later, there is still a Moslem minority in Greece - in other words, they still behave and are treated like a minority. The truth is that Greece has never behaved like its European Union counterparts in cultural terms, so it is not surprising that cultures do not integrate so much as they do in western countries. But the main reasons for this situation - having a recognised Moslem minority in Greece - is of course politics, directly related to the Treaty of Lausanne in our case. If you think of how modern Greece was born (through successive war campaigns), it becomes easier to understand why the permanent Moslem minority of Greece is still living in its own world. They can attend 'minority' schools, where they are taught 50% in Greek and 50% in Turkish, regardless of the fact that Turkish is not the mother tongue of all the Moslem minority in Greece, nor do all Moslems in Greece identify with Turkish ethnicity. The Pomaks, for example, have been proven genetically not to be of Turkish heritage; during the recent lockdown, prominent Turkish politicians were made unwelcome when they stated their intention to visit the Pomak villages in Greece. But the Pomaks are not Greek heritage either: they had been an integral part of the people that make up Bulgaria - until the borders changed, and they were now living in Greek territory. The Pomak language was supposedly an unwritten one until only recently (using Latin script). But successive Greek governments have referred to Moslems collectively as Turks, since they also speak Turkish (because they are learning it at school). There is also a small number of people of Turkish heritage living in the Dodecanese islands but they don't have the option to attend minority schools: Italy was in possession of the Dodecanese until 1948 when they were handed over to Greece, and Italy was not party to the Treaty of Lausanne, so the Moslems of the Dodecanese were unable to maintain the privileges of their minority status. The linguistic factor involved in the education of the Moslem minority of Greece also leads to interference from Turkey, due to the religious factor and its proximity to the country. |

|

|

|

From what I saw of the various Moslem Greek citizens that I came across in Thraki, they are very proud of their heritage and their home country, which is Greece. They generally don't intermarry with Greeks, but the cultures coexist peacefully. Given their knowledge of Turkish, they often study in Turkey. The places where each group predominantly resides in Greece is also a reason for their continued non-integration - they can live in their own enclaves if they choose, similar to how many Greeks continue to live in their ancestral towns and villages. We have all become more mobile only in more recent times. The different cultures that make up the Greek Moslem minority (Turkish, Roma and Pomak) are in fact very different from one another, and they are all very strong, just like the Greek culture, and hence they keep their own ground (helped even more so nowadays by the rise in identity politics); culturally, we don't see each other as the same, but we can coexist. |

|

|

|

During our trip in northern Greece, we decided to base ourselves at one point in the city of Xanthi. We like to stay in rooms similar to the kind we own and operate in Chania, which is how I ended up booking a room (it was actually a small semi-detached house) in what was clearly a Turkish neighborhood in Xanthi, something I had no idea about when I initially made the booking. I noticed a mosque in the map, but it never occurred to me that this would be a predominantly

Moslem neighbourhood. This concept is unknown to us in Crete. The owner, Murat, was of Turkish heritage: "Our family has been in the Balkans since 1364", he told us, in perfect Greek (albeit with an accent). "We weren't ανταλλάξιμοι ('exchangeable'). My wife is from a neighbouring village. I became a ship's electrician and am now retired. My daughters studied in Istanbul; one is now working in Moscow while the other is working for a TV station in Athens. I've been living in this neighbourhood all my life. Our neighbours are my aunts, uncles and cousins. We are all Greek citizens." While we stayed there, we heard Turkish being spoken all around us. Some women wore a hijab and pantaloons. There was a mosque on the road below our house and at various times of the day, we could hear the imam's call for prayer - we actually heard at least three imam calling at the same time from the different mosques in the city. The call is recorded: it is a reminder for people to pray, and not a call to go to the mosque, according to the modern rhythms of life (which are based on our work routines). The architecture of the houses in the neighbourhood was also interesting: they had much smaller windows than we are used to, and courtyards were not visible from the road - their view was blocked by walls and high gates. (I could show you the house we stayed in on Google maps, but it has been completely renovated since Google last visited - a decade ago! - and so have the houses around it). |

|

|

|

The villages of the Pomak people are found all over Thraki, near Greece's mountainous land border with Bulgaria, in the administrative regions of Xanthi, Rodopi and Evros (which make up Thraki), and naturally there are also Pomak villages in southern Bulgaria - this shows how borders affect ethnicity. When in Thraki, one of the most popular must-do's is in fact to visit the Pomakohoria, and we managed to visit a large number of them. The Pomak villages in Evros are more 'traditional' (because they are more remote), while the ones in Xanthi are actually much more 'touristic' - they are often showcased in tourist guides, and hence have become synonymous with the term 'Pomakohoria'. The villages remain remote, mainly because they are all found in mountain regions that are difficult to access, and this does not have to do just with the road network. In the past, they were the subject of suspicion and prejudice because they were Turkish-speaking (due to the educational system) and their association with Bulgaria was regarded in light of the cold war (communist politics). Until the early 1990s, the Pomaks were subject to the politics of the 'bara': although they could leave their villages and work in the city of Xanthi, they had to show identity cards in order to be allowed to re-enter their villages; there was a boom barrier guarded by the Greek military at the entry point for the Pomak villages. In other words, there were borders within the border of the same country, and the Pomak villages were not visit-able. (It reminds me of the way the covid crisis was handled in the beginning of the pandemic, where we could not travel inter-regionally.) This has now all changed, and in recent times the road network has been improved, but some Pomak villages remain remote to this day, as we discovered when we lost our way in the Pomakohoria of Evros - some roads connecting the Pomak villages are still dirt tracks. |

|

|

|

We asked Murat about the road conditions before our visit to the Pomakohoria of Xanthi to avoid the situation we were confronted with in Evros, especially because it was raining on that day (the only day it rained during our holiday). He even led us to the first one where he had business to attend to. Sminthi is the administrative centre of the Pomakohoria of Xanthi, and it has become quite built up for a village. The narrow road was filled with cars. Murat was helping someone who lived in Germany with their Greek property rights; as EU citizens in the Schengen area, many Pomak now live and work abroad, coming back to Greece mainly as expats to spend the summer in their ancestral homes. At Sminthi, we found a bakery where we stopped to pick up some breakfast. The shop assistant was delightful: "Where are you from? Oh, you are from Crete! You must have a lot of tourists there, it's been very difficult for us here in covid times, they closed the border from Bulgaria which leads to Xanthi, and we have lost that part of our livelihoods, very few strangers pass from here now". She offered a lot of information to us: "Tobacco plantation was the main work here, but because the work wasn't paying well and prices for tobacco fell dramatically, it's now all gone to Bulgaria and the greenhouses in Holland, and our own people have gone there, we still work on the land here, mainly in olives and vines, but because we are also much better educated now, we find better work opportunities, and things are improving all the time, life has changed since my parents' and grandparents' time. We live like the average Greek, except that we have a different religion". We thanked her for the conversation and continued on our way. |

|

|

|

Life was very quiet as we drove through the Pomakohoria, partly because of the rain, and because it was winter. Signs of life came mainly from a smoking chimney, a collared dog on the roadside, clothes hanging out to dry. We passed a school where a woman was waiting outside, presumably to pick up children as it was nearing lunchtime. Most Pomak villages now have multi-story houses, separate living spaces for each family member and their families. The area is densely forested, and autumn was a perfect time to visit to enjoy the changing colours of the leaves. Ehinos is the biggest village in the area with three mosques - their tall minarets stood out prominently - and a very pretty church near the river. There was also a memorial for a very important battle site in WW2; the German army needed three days to capture Fort Ehinos (Οχυρό Εχίνου), with 10-fold loss of life compared to the Greek army, and countless wounded. Murat told us of the brave patriotism that his people felt towards the country: "We are much more patriots than the locals!" he laughed. "We are one of the most peace-loving minorities in the world in my honest opinion," a belief that came from his many travels as a sailor all over the world. "Our parents and grandparents served this country, safeguarding the borders, all along the border with Bulgaria." He wished he had time to take us to the offices of the minority, where the records are kept of the people died defending the country's borders: "So many people from the minority have given their blood to safeguard Greece" he told us. |

|

|

|

I wasn't sure if we could expect anything to be open for lunch in the area, but Murat had insisted that we would find something in at least one village. Despite there being no sign of life in the area, the lights were on in a building with a restaurant sign in the village of Τhermes (which is known for its hot springs), called O Kalemtzis. A Pomak woman could be seen preparing food in the back kitchen. A young man asked us if we were vaccinated and led us to a table. We were the only customers indoors - 2-3 more tables were also occupied outside (in the rain). The menu had typical Greek fare, as well as a side dish often served in the north: 'Ougareza', which basically means 'Hungarian' - pickled cabbage salad. By the way there are hot springs all over this area but the main ones are in Ano Thermes, around an area called Iamatikes Piges. There is a very nice pool right by the Kalemtzis restaurant and the waters are known for their healing properties. |

|

|

|

The road leading from Xanthi to the Pomakohoria goes as far as Medousa, and after that, there is a dirt track which is drivable, but we decided not to take it. It is busy only at weekends when Tzemil opens his restaurant there in the village of Kottani. No one lives in Kottani any longer. Kottani is a special village for Murat: "After the mud road that takes you up to Kottani, there are more Pomak villages there, but below that, there are another 8-10 villages which are Turkish, that's where my great-great-greats came to live, and eventually, they came down to Xanthi after that, many many years ago. Thraki is more than just multicultural - it's multi-multicultural. Our origins are from Karaman in Ikonio (Ikonya in present-day Turkey), the same name Karamanlis (an important Greek statesman) gets his name from, and we came to the Balkans while the Ottoman empire was still in its heyday, and we've been here since 1364, that's what history says, and since then, we are still here, we love our home, and I especially love Xanthi, my neighbourhood, my 'magala', and for this reason, even though many opportunities presented themselves to me, I never stayed abroad, I've been everywhere as a sailor except Oceania, and I never stayed on, despite the opportunities I came across, because I always had a nostalgia for my hometown, that dirty filthy town as it once was, and my neighbourhood, which is the acropolis of the town, this is the best part of the city to see it from above." And he is right. We were so lucky to stay at Murat's house. |

|

|

|

Murat also told us the darker side of being a member of the Moslem minority. According to the reigning government, the Moslem minority was classified in different ways: "We used to think of ourselves as Turks here, then the government placed a label on us. We became one of three minorities: Pomak, Roma and Tourkogeneis (Turks by heritage). About two decades ago, they baptised us all Moslems, but you too can be a Moslem, a person who believes in God, as laid down by the prophets. My origins are Turkish... I like people for who they are, I don't care where they are from, their colour, their beliefs, I only care about their humanity. Until the mid-1990s, we didn't have the right to buy property, we couldn't get a driver's licence, we couldn't build a house; even if you had money to invest in soil, in property, in a house, you weren't able to. When my wife was pregnant with our first child in the early 1980s, I didn't have a kitchen, and even though I had made a lot of money, I wasn't allowed to extend my house, so I built a rough kitchen, by oiling the cogs so to speak, you had to find a local to go the services to beg on your behalf, to allow Murat, Hassan, Ahmed to let him build a toilet, or a kitchen, my wife was in her ninth month, she was ready to give birth, and I didn't have a kitchen, can you imagine what we went through!" No we can't, because a kitchen comes first in Greek homes. But these policies need to be examined under the eye of a tit for tat policy: both Greece and Turkey tried to find ways to silence the minorities in each respective country; from 130,000 Greeks left in Istanbul, there are now about 3000 left, whereas in Thraki, from an initial 100,000 people, there are now about 200,000 (1 in 3 citizens) who are Moslem. "We don't bear grudges," he continued, "we love Xanthi and Xanthi loves us." Life is now very different for the Moslem minority of Greece, and we have our membership of the EU to thank for that. They form an active role in the workforce, and we saw signs of this all over Thraki, wherever we went. |

|

|

|

Xanthi is a truly amazing city. We loved the narrow roads of the old town and the character of the buildings, especially the stately family home of the composer Manos Hadjidaki (his father was Cretan). The most amazing desserts from the 'polis' are served here: seker pare, kazan dipi, suzouk loukoum, and the heavenly kunefe. These desserts are not available where we live in Crete. They are authentic Turkish desserts, and they are made to tradition. Many of the ingredients used in them come straight from Turkey, as the shop assistant explained to me. In fact, there is much trade between the north and Turkey, which means cheaper prices, but in no way does that compromise the standard of living in Xanthi. We also ate at the famous restaurant To Pilima, just 20 minutes out of Xanthi, in the village of Pilima, set in beautiful landscape. It was developed by a local resident of Xanthi, Odzian Kara. He has received many accolades for his efforts to retain tradition in a natural environment, in combination with high quality restaurant dining. The food was highly exotic, reminiscent of Greek tastes with Turkish names. I didn't manage to visit the superb art installation at the House of Shadows but I can put that on my list for the next visit. Surely there will be another one. |

|

|

|

One of the best times to visit Xanthi is during Aprokreas, or Carnival Season when they have the second biggest celebration in Greece, after Patras. It lasts two weeks and features music, dancing, theater, parties, costumes and parades and reaches a crescendo with the parade on the final day and the night closing ceremony at the Kossynthos river bridge with the re-enactment of an Eastern Thrace custom, To kapsimo tou Tzarou (the burning of Tzaros) followed by a spectacular firework display. Xanthi is known for its nightlife anyway but during Apokreas they take it to another level. See also Activities in Xanthi |

|

|

Where to Stay in XanthiI highly recommend Murat's Safe and Cozy Studios in Xanthi! not just because of the hospitable, kind and informative owner but because it is one of the highest rated places to stay on Booking.com and is convenient to the center, is clean and fully equipped and in a quiet neighborhood. If it is full you can also try one of these highly rates hotels from Matt's Hotels of Greece Thrace Page. |

|

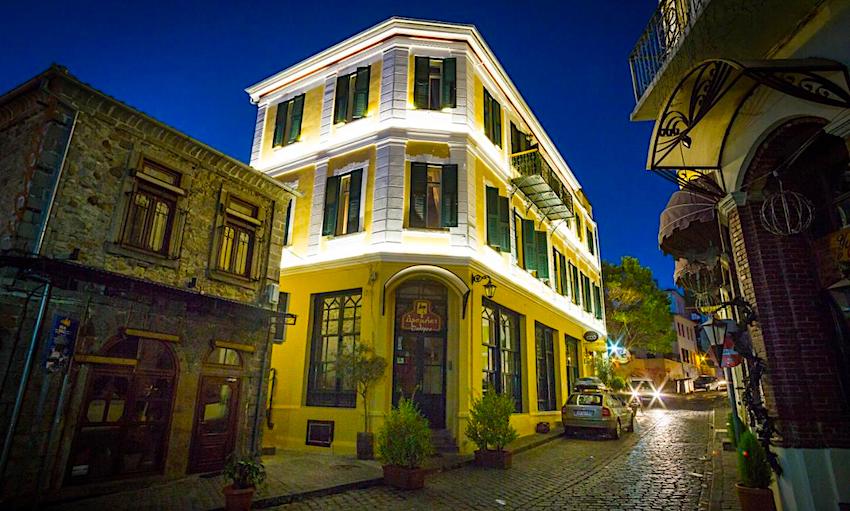

The Boutique Hotel 1905 (above photo) has a restaurant, allergy-free rooms, and free WiFi. The property is 1,000 feet from Municipal Gallery and 1,000 feet from Emporiou Square. The property is close to popular attractions like Clock Tower, Mitropolis Xanthi and Xanthi Town Hall. Rising Sun studios - Old Town has garden views, free WiFi and free private parking, set in Xanthi, 650 feet from Xanthi Old Town. Accommodation is fitted with air conditioning, a fully equipped kitchen, a flat-screen TV and a private bathroom with shower, a hairdryer and free toiletries. A microwave and fridge are also offered, as well as a kettle and a coffee machine. Boasting city views, Main Square Flat - LUXURY APARTMENTS XANTHI LAX offers accommodation with a patio and a kettle, around 650 feet from Folk and Anthropological Museum. This property offers access to a balcony and free WiFi. This air-conditioned apartment is fitted with 1 bedroom, a satellite flat-screen TV, a dining area, and a kitchen with a fridge and a stovetop. Surrounded by traditional restaurants and café-bars, Elisso Hotel is located in the old city of Xanthi. Boasting free Wi-Fi, the stylish rooms and suites offer a balcony with mountain views or the surrounding area. Fitted with Cocomat mattresses, each of the spacious guestrooms is air conditioned and heated. They have a safe, flat-screen satellite TV, minibar and electric kettle. Bathrobes, slippers, hairdryer and toiletries stock the bathroom. Located amongst oak and pine trees in Panagia Kalamou, 5.3 miles away from Xanthi, 916 Mountain Resort offers stone-built houses with fireplace and a balcony overlooking Mount Rodopi. A kitchenette with cooking facilities, dining area and electric kettle is included in all apartments at the Mountain Resort. Each has BBQ facilities and an LCD TV. |

|

For more about Thrace see Maria's article on Evros and Matt's article on Alexandroupoli |

Help Support Matt's Greece Guides

Do you enjoy using my site? Have you found it entertaining as well as useful? If so please show your appreciation by booking hotels through the travel agencies and the links found on my Hotels of Greece site. The small commission I

make on the bookings enable me to keep working and in most cases you won't find them any cheaper by searching elsewhere.

You can find

hotels in Greece by location, price, whether or not it has a swimming pool, and see photos and reviews by using this link to booking.com which also contributes to my website when you book. If you are appreciative of all the free information you get on my websites you can also send

a donation through Paypal or Venmo

Join Matt Barrett's Greece Travel Guides Group on Facebook for comments, photos and other fun stuff. If you enjoy this website please share it with your friends on Facebook and other social media.